- Diagnostic Imaging Vol 32 No 4

- Volume 32

- Issue 4

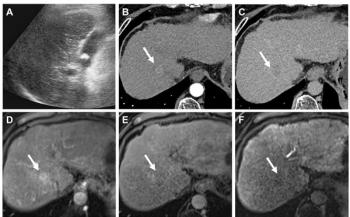

New US technique predicts chemotherapy response

A new ultrasound technique that measures cell death, tumor elastography, and vascular patterns can better predict how well cancer patients are responding to chemotherapy, Canadian researchers report.

A new ultrasound technique that measures cell death, tumor elastography, and vascular patterns can better predict how well cancer patients are responding to chemotherapy, Canadian researchers report. Typically it takes four to six months to determine response to treatment; the new technique shortens that to one to four weeks.

Rather than making a patient undergo expensive rounds of chemotherapy for six months, physicians would be able to tell right away whether the tumor is responding, according to the developers. Right now medical oncologists can’t make those decisions easily because they don’t have any quantitative imaging tools to guide them.

Michael Kolios, Ph.D., a physics professor at Ryerson University, and Dr. Gregory Czarnota, a clinician scientist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center, both in Toronto, ON, found that when cells die, their acoustic properties change and those changes are detectable via ultrasound.

When the cells break down, the nucleus condenses, fragments, and breaks into tiny pieces, changing the ultrasound images. At first the dying tumors become brighter.

Also, by applying quantitative measures to analyze the ultrasound images, one can extract parameters that could be used to quantify cell death, Czarnota said.

The parameters they are using are midband fit, spectral slope, the zero MHz intercept, and elastography and vascular patterns.

In their phase I clinical evaluation, Czarnota and Kolios are examining women with large, locally dense breast cancers, 5 to 10 cm in size, by measuring cell death, tumor elastography, and vascular patterns. In Canada these women are treated first with chemotherapy to shrink the tumors and make them more manageable for surgeons.

Typically these patients undergo a four to six-month course of chemotherapy, Czarnota said. There’s no standard imaging approach to determining their response to chemotherapy.

“What typically happens is the tumor is felt by the physician. It’s very difficult in these situations to determine if the tumor is responding or not,” he said. “It might get a little softer or not.”

In their study, Czarnota and Kolios are scanning the patients before chemotherapy and then five times after starting chemotherapy at weeks one, four, eight, and a couple of months after that.

The ultrasound technique uses conventional clinical-frequency ultrasound, but requires access to radiofrequency data.

“The data is coming right from the transducer, before it’s converted into an image,” Czarnota said. “That’s what we’re analyzing.”

Most radiofrequency data are thrown away by conventional ultrasound machines, but there are some companies, like Ultrasonix, that offer access to the raw data before it’s converted into an ultrasound image with the push of a button.

“These methods are not clinically approved for making decisions on the basis of chemotherapy,” Czarnota said. “That will have to come as a result of the research.”

Czarnota and Kolios are still looking at their data from 20 patients, but with at least the first five patients, the researchers can surmise how well the tumors respond in one to four weeks. They plan to expand their study to 50 patients.

“Hopefully within two to five years we’ll be evaluating changes on chemotherapy,” Czarnota said. “We’ll be testing it to customize chemotherapy, if everything pans out OK.”

Articles in this issue

almost 16 years ago

Philips' first quarter offers hope for better imaging marketplacealmost 16 years ago

MR spectroscopy readies role as cancer diagnosis, treatment toolalmost 16 years ago

What's old is new again, and the world rolls onalmost 16 years ago

Three decades take MRI from cutting edge to sustainabilityalmost 16 years ago

Mobile image display pioneer blazes regulatory path at FDAalmost 16 years ago

Dose-saving technologies proliferate throughout CTalmost 16 years ago

CT found effective for Dx lung collapse in womenalmost 16 years ago

Abdominal plaque reveals coronary artery diseasealmost 16 years ago

Modifying technique cuts radiation dose for CTAalmost 16 years ago

ACR launches breast MR accreditation programNewsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.