Fading FAST: emergency departments prefer CT protocol

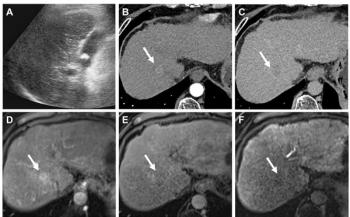

For years, the focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) protocol enjoyed a pre-eminent role in blunt abdominal trauma imaging, but it is losing favor as CT becomes more common in emergency rooms. Research presented Monday suggested the days may be numbered for FAST.

For years, the focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) protocol enjoyed a pre-eminent role in blunt abdominal trauma imaging, but it is losing favor as CT becomes more common in emergency rooms. Research presented Monday suggested the days may be numbered for FAST.

The paper, which included journal and database reviews, found that FAST demonstrates an overall sensitivity of just 79%. Studies relying on a single reference test report a sensitivity of only 66%, researchers found.

"Ineffective, inefficient, but still, recommended: Isn't it time to abandon focused abdominal sonography for trauma?" was the provocative title given by the authors, a research team based in Unfallkrankenhaus, an emergency hospital in Berlin.

"FAST has poor sensitivity and does not affect patient-centered outcomes in subjects with suspected abdominal or multiple trauma," the researchers concluded.

The concepts behind FAST date to 1974. It became particularly popular in the 1990s, said the principal author, Dr. Dirk Stengel. It was often used to scan for free fluid in the abdomen as an alternative to laparotomy.

But the growth of CT and its use in the ER may be reducing enthusiasm for FAST. During the scientific session in which the paper was presented, no one came forward to defend the ultrasound protocol, and the study was the only one devoted to sonography. Another eight papers covered CT and compared CT with other modalities in the ER.

The authors reviewed 957 diagnostic accuracy studies, selecting 62 studies representing 18,167 subjects for their analysis. The data encompassed two trials and 1037 patients for primary endpoint analysis (mortality). The relative risk in favor of the no-FAST arm was 1.4.

Dr. O. Clark West, session moderator, said there may still be occasions where FAST makes sense. A seriously injured patient who cannot be stabilized may be sent directly to surgery after a FAST scan, skipping the CT scan that would otherwise be conducted prior to surgery. But that happens only once a month at the Houston facility where he practices. If the patient is stable, the protocol calls for CT, West said.

Readers respond

I was referred by a colleague to your article. I was confused reading it; in the United States the FAST exam has never had a "pre-eminent" role in trauma evaluation.

If anything, its star is on the rise. The article was limited in

discussing the methodology and all endpoints employed in the studies

mentioned.

Often literature from non-clinicians suggest a low sensitivity for FAST,

but low sensitivity for what? If you look at all prospective trials published, the accuracy of FAST done contemporaneously with the criterion standard, you would find that

for free peritoneal fluid, the sensitivity of FAST is over 95% and for need for therapeutic

operations it is nearly 100%.

In our randomized, controlled trial (in press), including FAST in the evaluation reduced time to the OR, CT use, and charges.

In many respects, CT is a superior test, but its more expensive and, therefore, sending everyone to CT is unlikely to be cost-effective.

--Larry Melniker, M.D.,

Department of Emergency Medicine,

New York Methodist Hospital, New York

I found your article on the FAST exam vs. CT interesting, but must say it reflects a misunderstanding by the discussants of the use of the FAST exam in the critically ill trauma patients.

The FAST exam, in my opinion, has its primary utility in the unstable trauma patient who cannot go to CT scan. In these cases, it replaces another procedure, the Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage (DPL), which requires an incision and placement of a catheter into the abdominal cavity.

The FAST exam is much less invasive, is quicker, and appears to be as least as accurate as the DPL based on the limited data that is available.

Anyone who suggests that the FAST exam can replace a CT scan (and I don't know anyone who does) doesn't understand the limitations of the FAST exam.

The FAST exam also may be helpful in two other trauma scenarios: the patient who is being observed for possible intra-abdominal trauma but is not considered ill enough for a CT scan, and in multiple casualty incidents where it is used to triage critically ill patients when not all can get a CT scan in a timely manner. These indications have not been studied in depth.

--Michael A Peterson, M.D., FAAEM,

Director of Emergency Ultrasound and Emergency Medicine,

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.