|Slideshows|June 1, 2009

Credit Crunch Spurs Innovation

Author(s)James Brice

Advertisement

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.

Advertisement

Latest CME

Advertisement

Advertisement

Trending on Diagnostic Imaging

1

Leading Breast Radiologists Discuss the Recent Lancet Study on AI and Interval Breast Cancer

2

Is AI Better Than Neuroradiologists at Evaluating Aneurysm Growth on CTA and MRA Scans?

3

Diagnostic Imaging's Weekly Scan: February 1 — February 7

4

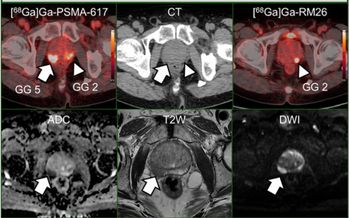

Comparative Study Shows Merits of PSMA PET/CT for Local Staging of Intermediate and High-Risk PCa

5