Level 10 Problems for Radiologists (and Why You Might Want to Avoid Them)

If you knew the daily level of challenges a radiology supervisor or manager encounters, would you still aspire to the role?

A podcaster I like returned to the airwaves last week. He had taken about a year off to pursue a high-level job for which he was uniquely suited. It was for the challenge and “love of the game,” not a big payday.

Such things have plenty of details that can’t be shared with an audience (NDAs and the like), but he was still able to satisfy some curiosity. One of his first bits was about the experience of dealing with what he called “level 10 problems.” I don’t think he coined the term, but when I tried looking it up, I found a lot of self-help stuff that wasn’t particularly relevant.

His version (and that of whoever he had gotten it from) went something like this. Imagine all of the problems, issues, challenges, etc., that you might encounter to be categorized on a scale of 1 to 10. One is the easiest, most readily solved, and 10 is the thorniest, most complex mess imaginable.

As an individual (say, a 1099 radiologist like myself, reading cases on a per-click basis), you encounter the gamut from 1 through 10. The lower numbers are far more frequent and might barely be speed bumps in your day.

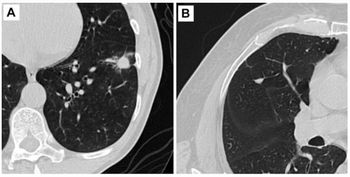

If you haven’t, say, committed the Fleischner Society guidelines to memory and you see a pulmonary nodule, you might have to take a moment to look them up. The nodule precisely fits some category or other, you report it out and move on the next case. That is a level 1 problem. Maybe your nodule(s) aren’t quite so cut-and-dried, and you have to puzzle over the guidelines to decide what fits best. That is a level 2 or 3 problem.

Other low-level problems we encounter include: suboptimal function of voice-recognition or PACS software, stuff that can be fixed with tweaking settings or discovering workarounds; flaws in a peer-review system that ding your stats or otherwise vex you until you learn ways to avoid such “gotcha” moments; and ergonomic issues that you can fix with new chairs, desks, etc.

Sooner or later, you get problems of a higher level that you, personally, can’t fix without excessive time/effort or collateral damage that may occur from overstepping your bounds. Unless you decide to just live with those problems, the next move is to kick them up the chain of command (or perhaps to someone outside of your own hierarchy who is better positioned to fix them). Whoever gets the problem has the authority and tools to address it.

That might be IT dealing with stubborn technical troubles that you can’t figure out (or that require “administrative” privileges you don’t have). It could be a technologist supervisor to handle persistent issues of folks not adhering to scanning protocols, pulling prior exams, etc. Rads in leadership positions might be your go-to for issues like work schedule, turf battles, and even disharmony with other rad colleagues.

Whoever it is, these folks may have their own low-level problems but the ones they get from you are all of higher number. By default, you were able to solve your lower numbers and screen them out of your “help me with this” list.

Sometimes, whatever you have given them is at a level even above theirs. Suppose you and perhaps your coworkers have repeatedly had issues with referring clinicians insisting on performing studies the wrong way. Appropriate contrast, modality type or what constitutes a STAT are common examples. Your department’s people might not have the clout to summarily overrule the surgeons or ER on a daily basis. This high-level problem goes further up the administrative ladder for interdepartmental action.

By the time problems have reached section heads or administrators, even more filtering has happened. They might only be getting levels 7-10 problems because the easier stuff was able to be solved by their subordinates. On the rare occasion they get a level 5 issue, they might breathe a sigh of relief and enjoy a moment of easy living.

If you are in a command position of a sufficiently large organization, you pretty much only get level 10 problems. With all of the easier stuff addressed before it reached your desk, everything you receive is ugly. No decision you make is going to be met with universal cheers from the rank and file. You are constantly picking winners and losers, no matter how fair you try to be. A lot of your compromises or make-do solutions will dissatisfy everyone to some extent.

Meanwhile, the folks in your organization who are dealing with level 1 and 2 problems all day don’t necessarily appreciate that you are constantly between rocks and hard places. They see a lot of the issues they punted to you as simple affairs with right/wrong answers. You were only needed to address them because of your authority, which they regard as a sort of superpower. When you fail to achieve what they thought should be a no-brainer solution, they can swiftly decide that you are not deserving of your position.

Radiologists, I believe, are particularly prone to this, because we spend much of our careers acting according to the notion that there are right and wrong diagnoses, and corresponding appropriate or inappropriate actions. Our QA stats routinely have us enjoying accuracy in the 95-99.9% range.

When we look at a highly positioned individual overseeing us and decide that, from our perspective, he or she is handling his or her problems to less than 50 percent satisfaction, we might conclude the supervisor is either incompetent or corrupt. We might decide we could do better than everyone we had answered to and get permanently frustrated that our health-care systems don’t recognize our capability to put us in the high-level hot seat.

Worse, we might actually get it and find out the hard way that a steady diet of level 10 problems is no picnic whatsoever. Then we get to deal with the harsh combo of a bunch of lower-level rads considering us incompetent or corrupt, and the abrupt awareness that we are at least as fallible as all of the rads we previously condemned from below.

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of radiology with the Diagnostic Imaging newsletter, delivering the latest news, clinical insights, and imaging advancements for today’s radiologists.