Articles by Greg Freiherr

Dose reduction will be among Siemens’ key messages at the RSNA meeting this year. Driving home this message will be IRIS (iterative reconstruction in image space), a proprietary algorithm that processes raw data acquired by CTs, according to André Hartung, Siemens vice president, CT Marketing and Sales.

“Surprise, surprise, surprise!” drawled an awestruck Gomer Pyle, taken off guard by the obvious way more than he should have been. Maybe that’s why this hound-dog–looking actor came to mind as I read a study indicating that hospital deaths drop when more imaging exams are done.

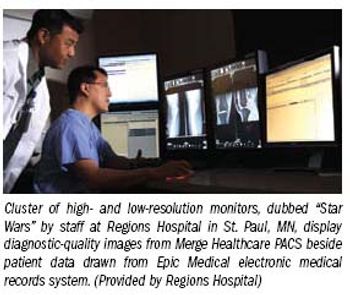

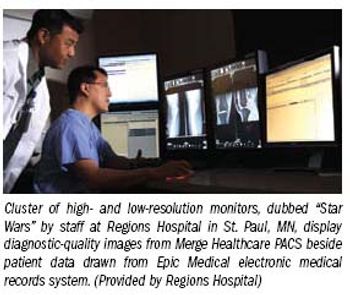

When Regions Hospital got serious about automating its patient record, administrators there decided that PACS would have to be part of it.

New twists on digital detectors spark vendors' hope for long-awaited commercial success.

Impact on patient safety, hospital stay lead list of vendor priorities for scanner enhancements.

Diverse capabilities in MR reflect the corporate philosophies of individual vendors, as well as how they see opportunities in the marketplace and seek to capitalize on them

A storm of public anger is brewing. The first signs are the gathering winds of dissent within the medical community against decades of sometimes shrill advocacy for breast and prostate cancer screening, winds that could easily blow up an indignant response from the American public.

I grew up believing that you get what you pay for. Look for sales, not knockoffs. Buy inexpensive, not cheap. Those were my shopping tenets, handed down by parents who lived through the Great Depression. After many years of believing this, I’m sorry to say the tenets may not actually hold, at least not in medicine.

A coalition representing imaging manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies, and professional societies fears a corporate tax embedded in the Senate healthcare reform bill could stifle product innovation, though the exact financial impact of the proposed surcharge is hard to gauge.

If current life expectancy trends continue, more than half of the babies born in rich nations today will live 100 years. Reaching the century mark is the natural extension of the huge increases in life expectancy—30-plus years—seen in most developed countries over the 20th century. Death rates in those with the longest life-expectancy, including Japan, Sweden, and Spain, suggest that, even if health conditions do not improve, three-quarters of newborns will live to see their 75th birthdays.

It should come as no surprise that the nuclear medicine community is struggling to keep up with the number of prescribed heart and bone exams. Technetium is typically used in the U.S. for more than 16 million nuclear medicine tests each year-but not this year. A survey by the SNM found that three quarters of nuclear medicine physicians are delaying patient tests, in many cases longer than a month. A shortage of medical-grade molybdenum-99 (Mo-99), the isotope critical to generating technetium, is the reason.

An MR technique that acquires data radially produces images of the breast with such detail that its developers at the University of Wisconsin believe it may eliminate the need for some biopsies.

Using logic that could just as easily be applied when considering a toddler, the federal government damned proton therapy on Sept. 14 with a report that brands the cancer treatment as lacking evidence of effectiveness and safety.

It’s the kind of research that radiology needs: a study performed at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine that documents enormous cost savings from the use of an image-guided procedure.

Sometimes it’s just better not to know. One of those times may be when you feel perfectly fine, but your brain scan comes back with something that looks bad. The problem: how do you know it’s nothing to worry about?

The argument that diagnostic technologies make a difference in clinical outcomes is like the one that eyesight is helpful when crossing the street. If you don’t see danger coming, whether it is a disease or car, it’s hard to avoid it. Most in radiology would agree that this certainly makes sense for preventive medicine. Another obvious argument applies to the diagnostic/therapeutic process. How can patients be treated if physicians don’t know what ails them?

Ask this question of someone in the U.S. radiology community and I’m willing to bet the answer will be spoken a bit louder than the question was asked. The premise is insulting-although apparently not to radiologists in Norway, or so I have been led to believe.

Recently the White House announced that the first chunk of money, $1.2 billion in grants, is set to prime the healthcare IT initiative in the U.S. The funds will begin flowing sometime next year. About half will go to establish HIT centers that will help hospitals and docs to build their own electronic medical records (EMRs). The other half will go toward developing a nationwide system of EMRs.

For the third time in less than a year, results from a retrospective study of breast cancer cases were framed as new research, challenging the routine use of MRI as a means to improve surgical outcomes in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. The results, announced in press releases in fall last year and twice this summer, bear repeating, said the principal author of the study, Richard J. Bleicher, co-director of the breast fellowship program at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia.

Three weeks ago I tried batting down a football thrown by a gifted young athlete whose pass floated higher than I could reach with both hands. The result made me appreciate how far digital imaging had come-and what was wrong with healthcare in this country.

They are so small the name “particle” doesn’t do them justice. They are called instead “nanoparticles,” tiny bits of matter—liposomes, actually—being groomed to carry cancer-treating radioisotopes to tumors. Last week in Anaheim, CA, at the American Association of Physicists in Medicine meeting, a group of researchers from Johns Hopkins University reported progress with this new type of nano-killers

The makers of imaging equipment will soon get a handle on industry-wide performance in the first half of 2009, tallying the units sold and revenue earned. They’ll put their numbers in the context of what they believe their competitors did and come up with a snapshot of where we, the imaging community, have been. I’m betting two bits to a donut it won’t be pretty.

There is a tendency to see imaging advances as disjointed pieces. With no master plan behind their development, these often very specific developments are launched into the medical mainstream like stones skipped across a river. Some make it to the other side and take hold in clinical practice. Others make a tiny splash and vanish.

Expectations can be a problem. This is especially so when the government gets involved.

Models based on the past can be helpful when trying to predict the future. So it has been with SPECT/CT.

Short-stay units are a relatively new development in the war against healthcare costs. They are designed for patients who require observation and short-term intervention but (probably) not admission to the hospital.

Radiologists who use imaging-related electronic record-keeping could qualify for some of the $19 billion in economic recovery money set aside for electronic health record conversion if they meet the federal government’s definition of “meaningful use” for their records.

It’s funny how we carry things with us from childhood. Growing up in my home in Wisconsin, it was common to hear my father say that the U.S. had the worst political system in the world … except for those in every other nation. We can say much the same today for our healthcare system. We have more advanced technology in a broader installed base than any nation in the world. But we’re nowhere near where we could -- or should -- be.

Vendors this week at the Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine meeting in Charlotte, NC, are offering a grab bag of technologies to meet challenges posed by the nature of medical imaging.

Interoperability and improved efficiency were the dominant themes of products and applications unveiled and demonstrated this week at the Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine meeting in Charlotte, NC. Vendors drew back the curtain on behind-the-scenes automation built into software, framing quick-click access to data as the means to improving communications among radiologists.